Update on Grave Concerns at the Boston Marathon

Is Increased Coronary Artery Calcification in Athletes Important ?

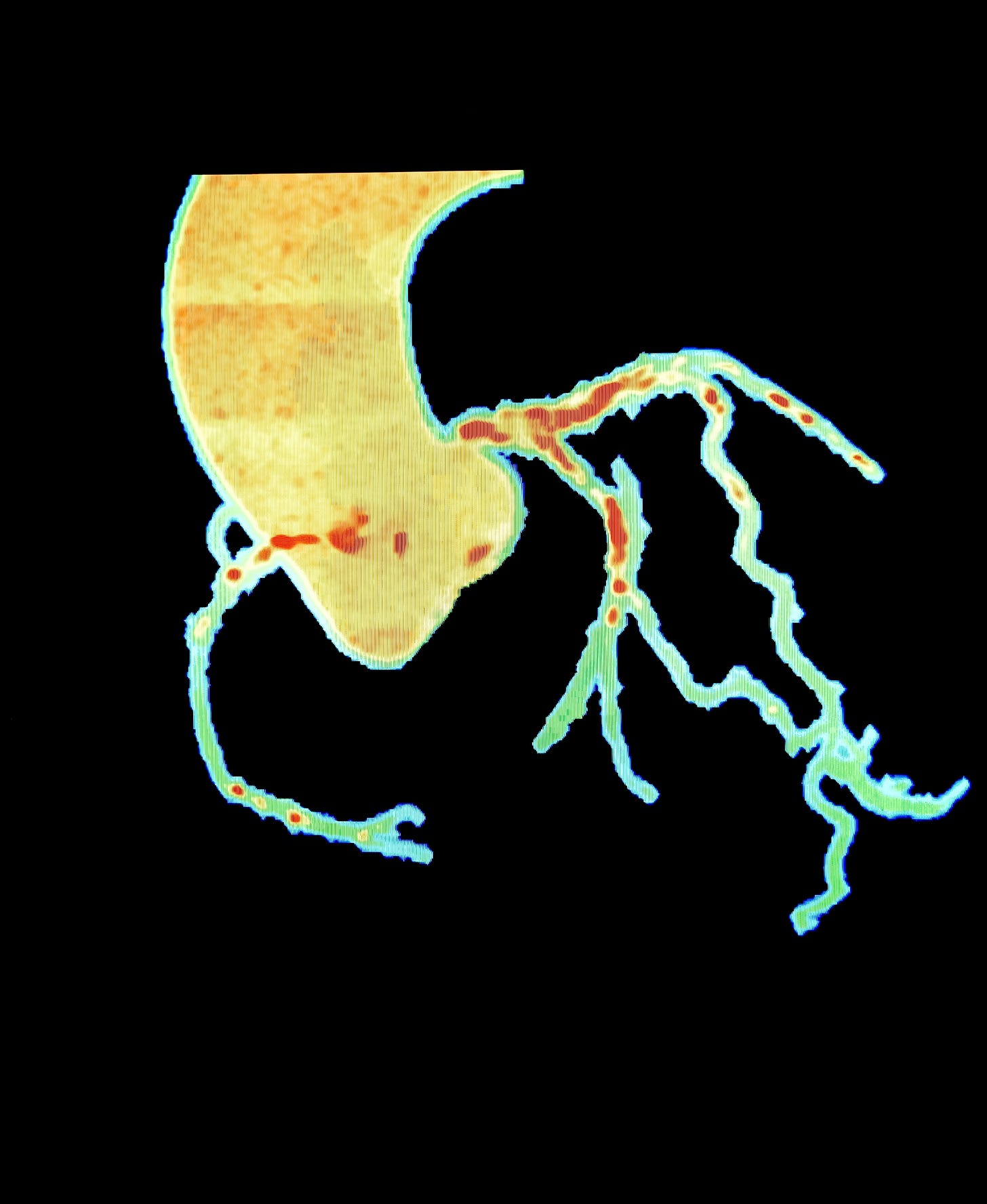

Reproduced by Subscription form Shutterstock

One of my favorite posts is “Grave Concerns at the Boston Marathon” (1) because it combines my interests in the history of sports, competitive distance running, and cardiovascular physiology. It repeats the story of Clarence DeMar, who won Boston seven times. He died at age 70 of cancer, but his autopsy as reported by the famous Boston cardiologist, Paul Dudley White, showed that DeMar’s coronary arteries were widely patent but had extensive coronary of atherosclerosis.

The idea that large amount of exercise might have deleterious cardiac effects is an apparent paradox. Exercise is associated with all kinds of beneficial effects. Jeremy Morris was a pioneering British exercise epidemiologist. He compared health outcomes in sedentary London bus drivers and the conductors, who repetitively climb the stairs on the double-decker buses. After a lifetime of such novel studies, he concluded that exercise was “the best buy in public health”. (2)

But early reports by Stephan Moehlenkamp in Germany (3) and James O’Keefe and colleagues at St. Luke’s Heart Center in Kansas City, (4) suggested that middle aged marathon runners had more coronary artery calcification (CAC), evidence of atherosclerosis, than their sedentary counterparts. There were methodological concerns with these early reports, and I was skeptical of the conclusions, but I and my colleagues from the Netherlands have summarized the studies on this issue and have concluded that lifelong endurance athletes have both more CAC and more non-calcified coronary atherosclerosis than their sedentary counterparts.

The mechanism is unknown but I have speculated that the larger heart size of the endurance athletes increases the excursion and twisting of the coronary arteries during cardiac contraction and that the resultant turbulence leads to atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is more likely to occur at places where there is disruption of laminar blood flow: the carotid siphon, the aortic bifurcation, and the coronary arteries. My hypothesis is purely speculative. The argument against this idea is that exercise training decreases resting heart rate, and slower resting heart rates are associated with increased longevity in multiple studies. Furthermore, my friend Polly Beer, MD, PhD, demonstrated that slower heart rates produce less carotid (5) and coronary (6) atherosclerosis. This was done when Polly was working with the renown Stephan Glagov. Dr. Glagov was the originator of the observation that atherosclerosis prompts the artery to expand to maintain blood flow, and that only after a narrowing of about 40% is the artery unable to compensate.(7). Polly reached her conclusion by studying atherosclerosis in monkeys whose heart rate was controlled by atrial-node ablation and implanted electronic pacemakers. My counter to this counter-argument is that the slow resting heart rate produced by exercise training is still associated with increased cardiac size, and the increased cardiac size would still increase coronary twisting and create turbulence during contraction. So, maybe the deleterious effects of heart size override the benefits of a slow heart rate in the athletes.

In my “Grave Concerns” post, I mentioned that the clinical significance of this increased atherosclerosis in endurance athletes was not known.

So here is the update.

Dr. Stephen Sidney from Kaiser Permanente’s Research group in California, Dr. Gary Gerber from Tel Aviv, their colleagues and myself examined the relationship between physical activity and coronary artery calcification in 3,141 participants in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in the Young Adult Study (CARDIA). Physical activity (PA) was determined by both self-report and accelerometer. Cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) was determined by treadmill testing. Cardiovascular events (CVE) were determined 13 to 14 years later.

Subjects who had higher CRF and activity levels had a reduced risk of subsequent CVE. In contrast to other studies, this study did not observe that more activity was associated with more CAC, possibly because these subjects were not “athletes”. Indeed physical activity was associated with a lower CAC, which was partly due to lower CVD risk factors. Those with high fitness and no CAC had the lowest risk of CVE, which is no surprise, but compared to this group, those with high fitness and CAC had a 468% increased risk of CVE, even after adjusting for socioeconomic status and cardiac risk factors. Similar results were observed when physical activity was substituted for fitness. These results demonstrate the higher CRF and activity levels reduce CVE, but that CAC even in highly active subjects is not benign.

Similar results have been reported using data from 26,724 participants in the Cooper Clinic Longitudinal Study by Ben Levine and colleagues. Individual physical activity was determined by self-report and used to create four activity groups. CAC scoring was performed to assess subclinical atherosclerosis. Acute myocardial infarctions, coronary revascularization and total mortality data were obtained from the Medicare database.

The prevalence of CAC scores ≥100 Agatston units increased with increasing physical activity consistent with the idea that high amounts of physical activity increase coronary atherosclerosis. Participants in the middle 2 activity groups had the lowest CVD event rates. But CVD rates in the most active subjects were not reduced compared with the least active group, and higher CAC scores increased the risk of CAD regardless of activity level. This again indicates that the high CAC scores observed in active individuals is not benign and has the same clinical significance as subclinical atherosclerosis in less active subjects. Total mortality was lowest in the most active group, however, demonstrating that exercise, despite accelerating sub-clinical atherosclerosis, does increase overall survival. I am impressed with this study and wrote the editorial that accompanied it. (7)

Both of these studies have issues. The CARDIA study did not study athletes. The Cooper cohort was likely a more active group, but the participants were aware of their CAC scores so it is possible that higher CAC scores prompted clinicians to more frequently diagnose myocardial infarctions and recommend revascularization.

Nevertheless, these two studies are the best evidence to date that the increased atherosclerosis and CAC scores in active individuals are not benign. But remember, that fitness and exercise are consistently associated with an increased lifespan. We cannot now, or probably ever, be able to determine if it’s the exercise itself or something about the people who exercise that is responsible for the apparent health benefits. I bet it’s both.

I discussed my clinical approach to managing highly active patients, primarily endurance athletes, with high CAC scores in my prior post. (1). Here is a summary.

1. Reassure the patient. Reassurance is great medicine.

2. Exclude other causes of the increased calcification. I get a calcium level and a parathyroid hormone level just to make sure that hyperparathyroidism is not contributing to the calcification. We have seen at least 2 patients with very high coronary artery calcification scores who were endurance athletes and who turned out to have hyperparathyroidism.

3. Treat the dickens out of the LDL cholesterol level. I tell the patients that I am going to lower their cholesterol level as low as possible. I call this “playing cholesterol limbo”; how low can you go without knocking the bar of the stanchions or how low can you get the cholesterol level without side effects. Also, look for, and treat, other risk factors. Lipoprotein (a) and “borderline” diabetes should be excluded. I think a lot of atherosclerosis is due to too-early-to-detect insulin resistance as discussed previously. (8)

4. Do an exercise test to exclude occlusive coronary stenosis if the athlete has any symptoms. I don’t routinely do an exercise test if the athlete has no symptoms during hard training, but if there are possible symptoms I always do an exercise test. We do not have revascularization studies specifically for endurance athletes, but it’s hard to find conclusive evidence that re-vascularization saves lives or stops heart attacks in the general population, although it does treat angina. To test or not to test is always a hard decision, so I judge each case separately.

5. Don’t totally restrict the athletes from continued sports participation. I do ask them to tone it down for a while to let risk factor reduction work, and to consider backing off from intense training and competition because they are “not going to the Olympics for free.”

6. Remind the patient that most of the health benefits of exercise training accrue at low levels of exercise. The prolonged, intense stuff is for fun but not necessarily for health.

1. https://pauldthompsonmd.substack.com/p/grave-concerns-at-the-boston-marathon

2. Morris JN. Exercise in the prevention of coronary heart disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26(7):807-814.

3. Mohlenkamp S, Lehmann N, Breuckmann F, Brocker-Preuss M, Nassenstein K, Halle M, Budde T, Mann K, Barkhausen J, Heusch G, et al; Marathon Study Investigators; Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study Investigators. Running: the risk of coronary events: prevalence and prognostic relevance of coronary atherosclerosis in marathon runners. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1903-1910.

Schwartz RS, … Roberts WO, O’Keefe HO. Increased Coronary Artery Plaque Volume Among Male Marathon Runners. Mo Med. 2014 Mar-Apr;111(2):89-94. PMID: 30323509

Beere PA, Glagov S, Zarins CK. Experimental atherosclerosis at the carotid bifurcation of the cynomolgus monkey. Localization, compensatory enlargement, and the sparing effect of lowered heart rate.Arterioscler Thromb. 1992;12(11):1245-53. PMID: 1420083

Beere PA, Glagov S, Zarins CK. Retarding effect of lowered heart rate on coronary atherosclerosis. Science. 1984 Oct 12;226(4671):180-2. PMID: 6484569

7. Thompson PD. Does Coronary Calcium Mean the Same in Active and Sedentary Individuals? Circulation. 2025 May 6;151(18):1309-1311. PMID: 40324033

8. https://pauldthompsonmd.substack.com/p/is-measuring-glucose-the-right-way

#athletes #coronaryarterycalcification #coronarycalcificationscore #exercise #physicalactivity #enduranceexercise #bostonmarathon #ClarenceDeMar

Hi Paul.

Thank you for your article.

I obtained a CAC score just to screen, and the score was 1600. No symptoms. Finished second in my age group in the 5th Ave mile, at age 77.

Main renal artery score 0. 3-400 in the other cornonary arteries.

I would offer 2 comments:

1. I did marathons for only 3 years, and since then 4 miles or less 4 times a week, but always at a vigorous pace. Studies seem to show that intense running is more closely associated with CAC than is long slower distance running.

2.Do you see any publications that consider the role of the substantially increased intake of food and particularly carbs as a result of the expenditure of so many calories with exercise?

NOT LIKELY A BIG MYSTERY: I would bet that the most active intake more animal protein with leucine (BCAA) and saturated fat causing inflammatory mTOR activation and cholesterol production -> cor ASCVD/calcification. HRS, MD, FACC